In the middle of an active volcano at the bottom of the world, dozens of fur seals bask in blowing wet snow. They are mostly unfussed by their two-legged guests.

Around them lie cockeyed iron tanks and wooden boats from an early 20th-century whaling settlement, so weathered they’re nearly absorbed by the black sand beach. Traces of Chilean and British bases appear just as humbled.

On the surface, Deception Island’s Whalers Bay is still humanity’s biggest imprint on Antarctica, outside of its 80 or so research stations.

But a climate scientist might say otherwise.

Studies on this fragile continent have documented how temperatures, glaciers, oceans and wildlife are reacting to the warming consequences of fossil fuel emissions. A place this remote and isolated makes a perfect laboratory for grasping the past, present and future of the Earth’s climate, according to many scientists drawn to Antarctica.

It’s a case study with high stakes, says Natural Resources Canada scientist Thomas James, who is leading the first all-Canadian expedition to the region.

“What happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay here,” he said, while recently walking the beach at Whalers Bay, as scientists gathered samples from the sand, snow and air around him.

Climate shifts ripple beyond Antarctica

It’s understood that climate change doesn’t acknowledge politically drawn borders. But James explains that Antarctica’s ice and cold oceans play an outsized role in regulating our climate.

Just this month, researchers identified that melting freshwater from Antarctica’s glaciers is altering the water chemistry of the Southern Ocean. They predict that the changed salinity will slow the vital Antarctic Circumpolar Current by 20 per cent by 2050. The strongest current on Earth, the ACC’s influence extends to the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans, pumping water, heat and nutrients around the world.

The current also protects Antarctica’s ice sheets — large masses of land-based ice — from warmer northern waters, preventing sea level rise, which would impact coastal communities around the globe.

“We know that the Antarctic ice sheet is potentially unstable and could provide larger amounts of sea level change than the present models currently predict,” said James. “It’s a huge reservoir of fresh water.”

He’s studied Antarctica for more than 30 years, but his field work has mainly been in the northern polar region; this is only James’s second time in Antarctica.

“We think that spending some time understanding the Antarctic ice sheet and the implications for sea level change is very important for Canadians.”

It’s not just ice sheets that are melting. Sea ice (frozen sea water) at the poles has reached record lows three months in a row.

“The fact that we’re now seeing a reduction in Antarctic sea ice is really just one of many, many indicators that global climate change is happening,” said James. “It’s happening in all facets of the environment, and in many cases it appears to be accelerating.”

Team of strangers contribute to climate science

James’s team of 15 scientists — many of them strangers before this expedition — cross numerous disciplines of science. They are studying not only the ice sheet but glacial melt, the ocean floor, contaminants like microplastics and the sea water itself.

Aboard the HMCS Margaret Brooke, they are supported by the Royal Canadian Navy, which runs the winches, cranes and boats to help the scientists collect a mass of samples around the South Shetland Islands off the tip of the Antarctic Peninsula.

It is part of the RCN’s larger Operation PROJECTION, to circumnavigate South America, strengthening alliances with other southern navies and gathering experience in the southern polar region.

Militaries may only enter Antarctica’s boundaries if they are supporting scientific research, a rule set out in the Antarctic Treaty, which governs the continent.

The Arctic and offshore patrol ship will only cover a small fraction of the continent over four weeks of maritime transit from Chile’s Punta Arenas, but the voyage and science work takes enormous effort.

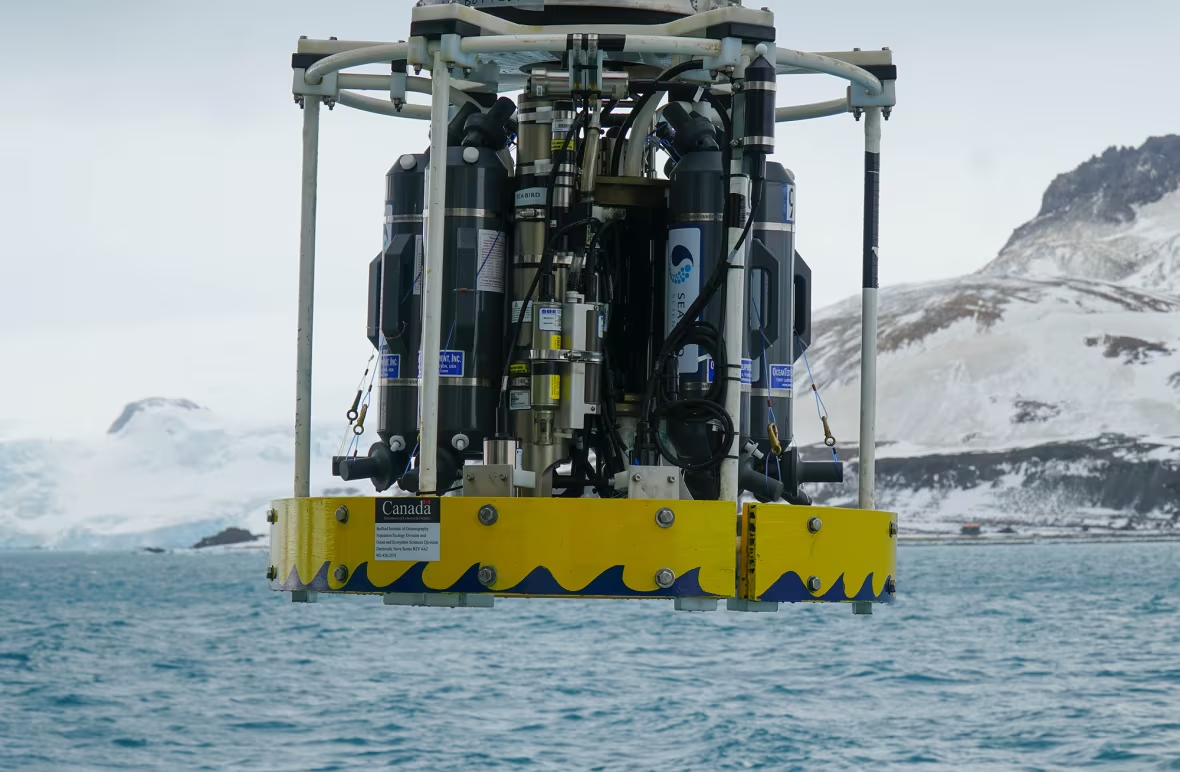

From early-morning trips on zodiac boats to glacier-lined coasts to late-night, deep-water collection using an elaborate crane, winch and boom system designed in Halifax, the science team is putting in long hours, determined to maximize their rare Antarctic access.

Brent Else is one of the scientists, here to study the ocean’s chemical properties.

“It turns out that oceans absorb a lot of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” said the University of Calgary researcher. “If you look back over time, sort of since industrialization, they’ve probably taken up about the equivalent of about 40 per cent of all of the emissions that humans put into the atmosphere. So that gives us a huge break on climate change. What we really need to understand is, will the oceans continue to do that?”

Because of its cold temperatures, the Southern Ocean has the ability to sink carbon to significant depths — and keep it out of the atmosphere — for hundreds of years.

“It’s really important that we understand what’s going on in polar oceans, especially because they’re changing the fastest,” said Else. “So in an area like Antarctica, as we start to get more ice sheet melting, that’s going to put more freshwater into the Southern Ocean. And that might affect how all of these things interact.”

On Antarctica’s Deception Island, Canadian scientists study the links between melting ice sheets and rising global sea levels, saying what happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay there.

It’s why the interdisciplinary approach of this expedition is so advantageous.

“Most science, by its nature, is incremental. And what we’re doing is adding to that body of knowledge,” said James.

The team will take back thousands of samples for analysis over the coming weeks and months. Many of them will go to other researchers back home in Canada.

Speaking about the groundbreaking expedition, James said, “It feels momentous.”